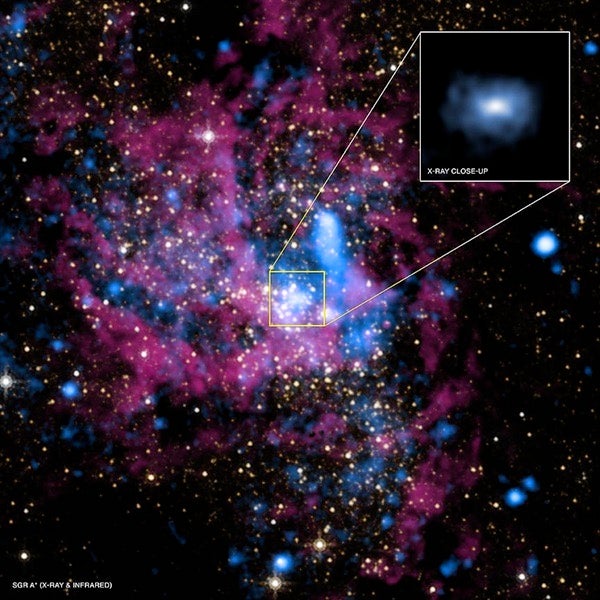

An image of the area surrounding Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy, in X-ray and infrared light. X-ray: NASA/UMass/D.Wang et al.; IR: NASA/STScI

The universe is filled with bizarre objects.

Then again, Earth is all we know. So what may seem wild and exotic to us is likely common throughout the cosmos. But that doesn’t take away from the fact that space is filled with many mysterious oddities that astronomers are just beginning to both discover and unravel.

So, without further ado, here is a list of just four (of many) contenders for the weirdest objects in space.

Weirdest objects in space: Black hole Sagittarius A*

Until recently, black holes seemed to come in only two sizes: either small remnants of collapsed stars or gargantuan beasts with masses of millions or even billions of suns. Only recently did astronomers confirm the existence of intermediate-mass black holes, but still, most black holes we observe are either petite or giant. An example of the latter sits at the center of every galaxy — including the Milky Way.

But while the supermassive black holes in many other galaxies radiate X-rays or violently spew huge jets of material, ours is strangely quiet. Too quiet, in fact, as if we’re hosting a sleeping monster.

Not that our galactic nucleus is a total mystery. While we cannot visually see what’s going on some 27,000 light-years away because it’s hidden behind impenetrable sheets of dusty gas, other wavelengths of light still leak out. Radio telescopes long ago detected an intense emission there, named Sagittarius A. The black hole, deeply buried within that radio noise, received the peculiar name Sagittarius A* or Sgr A*, which is pronounced “Sagittarius A-star.”

Sagittarius A* weighs about 4 million solar masses, which is less heavy than what lurks within the cores of most galaxies. Still, that much mass is impressively crammed into a spherical volume with a radius of less than 13 million miles (21 million kilometers) — half of Mercury’s orbit. As to the actual nature of this ultra-crushed singularity, or even whether some unknown process has halted its shrinkage and prevented it from attaining zero volume, no one knows. Our physics fails.

Weirdest objects in space: Pulsar planets

This artist’s impression portrays pulsar PSR B1257+12 as a small point of light in the distance, with its three planets bombarded by lethal X-ray and gamma-ray radiation. NASA/JPL-Caltech

What was the first planet found beyond our solar system? Astro-geeks usually cite the discovery of the Jupiter-mass planet circling the naked-eye star 51 Pegasi in 1995. But the truth is far stranger. Three years earlier, astronomers Aleksander Wolszczan and Dale Frail announced they had found not one but two planets — and these orbited the oddest kind of star in the universe, a millisecond pulsar.

Its name is PSR B1257+12, and it lies in the constellation Virgo the Virgin at a distance of 980 light-years. It spins 161 times a second and, like all pulsars, is a neutron star, the smallest and densest visible object in the universe.

No telescope was used in the discovery, at least not one that gathers visible light. Instead, the huge Arecibo radio observatory in Puerto Rico, with its 1,000-foot (305 meters) collecting area, carefully monitored radio signals from pulsars. (Sadly, Arecibo Observatory recently catastrophically collapsed following two cable failures.)

Electromagnetic energy streaming away from their magnetic poles sweeps around like a lighthouse beam, producing radio flashes with each rotation. These super-collapsed neutron stars are always less than 20 miles (32 kilometers) wide, with wild amusement park spins of dozens or even hundreds of rotations per second.

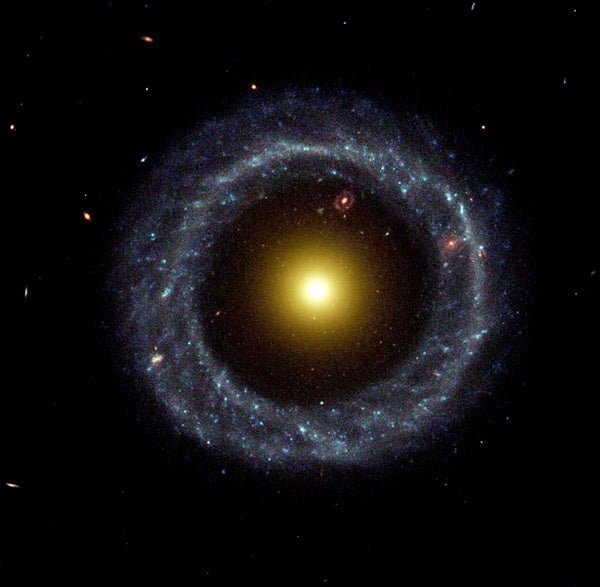

Weirdest objects in space: Hoag’s Object

This artist’s impression portrays pulsar PSR B1257+12 as a small point of light in the distance, with its three planets bombarded by lethal X-ray and gamma-ray radiation. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Galaxies are the largest things in the universe. Happily for us, they come in only a few varieties, making them easier to identify and theorize about. Nearly all are either elliptical (ball-shaped), irregular, or else spirals of various kinds. But a handful of oddballs fit none of these categories, and one galaxy stands all by itself.

In 1950, astronomer Arthur Hoag came upon a tiny, faint, 16th-magnitude ring surrounding a ball-like center, and reasonably assumed it was a planetary nebula — a nearby puff of gas expelled from a single old-aged star. However, later spectroscopic studies showed it was not. Hoag also thought it possible that this object was some sort of peculiar galaxy. And — as if to prove that if you make enough guesses, you increase your chance of success — his last surmise was right.

In 2002, the ultra-sharp optics of the Hubble Space Telescope revealed Hoag’s Object, as it is now called, as a perfect blue ring of stars, dust, and gas, complete with knotty clumps that are unresolved star clusters. In other words, yes, this is a galaxy. The problem, of course, is that Hoag’s Object does not assume the familiar spiral pattern, with arms wending their way inward to the older, yellower stars that make up nearly every galaxy’s nucleus. Instead, the nucleus sits all by itself in space. A whopping 70,000 light-years away from it, separated by near-nothingness, hovers that ring of billions of stars, planets, and who-knows what else.

Hoag’s Object lies 600 million light-years away from us in the constellation Serpens Caput, the rear half of the writhing snake held by Ophiuchus the Serpent Bearer. Its inner yellow core is 24,000 light-years across, almost the same as the core of our Milky Way. The outer ring of Hoag’s Object, with a width of 120,000 light-years, is similar in size to our galaxy’s diameter. It’s almost as if some malevolent alien starship vacuumed up the middle sections of a galaxy but bewilderingly spared both the center and the outermost regions.

Weirdest objects in space: Fermi bubbles

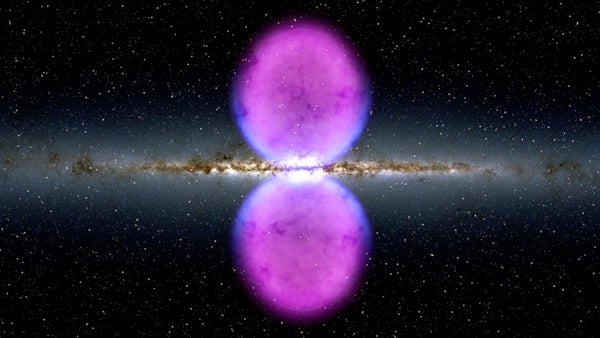

Enormous expanding bubbles of ultra-powerful gamma rays, each centered on nothingness, meet at our galaxy’s core, as depicted in this illustration of the Milky Way. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

In November 2010, astronomers using NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope announced an astonishing discovery. Emanating from the center of our Milky Way Galaxy are two bubbles made solely of powerful gamma rays.

This would have been strange enough if the bubbles, expanding at 2.2 million mph (3.5 million km/h), were concentric and centered on the galaxy’s core. But no, the two enormous spheres each hover in seemingly empty space above and below the black hole Sagittarius A* in the Milky Way’s nucleus. The bubbles are tangent to each other, touching at the galactic center to form a squat hourglass shape. The entire structure looks like the number 8 or a sideways infinity symbol.

With all the weird and wild objects in space, it’s impossible to pinpoint exactly which ones are the most bizarre. And thanks to astronomers’ tireless efforts, we’ll surely learn of even more exotic cosmic objects in the future — ones that could potentially shake up our understanding of the universe forever.