La ciudad de Heracleion fue tragada por el mar Mediterráneo frente a la costa de Egipto hace casi 1.200 años. Fue uno de los centros comerciales más importantes del Mediterráneo antes de hundirse hace más de un milenio. Durante siglos, se creyó que la existencia de Heracleion era un mito, de forma muy parecida a como se considera hoy la ciudad de la Atlántida. Pero en el año 2000, el arqueólogo submarino Franck Goddio finalmente encontró la ciudad hundida después de una extensa investigación submarina en la actual bahía de Aboukir.

Antes de este descubrimiento moderno, Heracleion había sido casi olvidado, relegado a un puñado de inscripciones y frases en textos antiguos de personas como Estrabón y Diodoro. El historiador griego Heródoto (siglo V a. C.) escribe sobre un gran templo que se construyó donde el héroe mitológico Heracles (o Heracles) pisó por primera vez Egipto. También afirmó que Helena de Troya y Paris visitaron la ciudad antes de su famosa Guerra de Troya. Cuatro siglos después de que Herodoto visitara Egipto, el geógrafo griego Estrabón señaló que la ciudad de Heracleion estaba ubicada al este de Canopus, en la desembocadura del río Nilo.

Franck Goddio founded the European Institute for Underwater Archaeology, and together they discovered the long-lost city of Heracleion off the coast of Egypt. ( Christoph Gerigk © Franck Goddio Hilti Foundation )

The underwater archaeologist Franck Goddio is known as “a pioneer of modern maritime archaeology.” Goddio founded the European Institute for Underwater Archaeology (IEASM) in 1987, with the aim to explore and research underwater archaeological sites. IEASM is known for having developed a systematic approach, using geophysical prospecting techniques on underwater archaeological sites. By exploring the area in parallel straight lines at regular intervals, the team can identify anomalies on the sea floor, which can then be explored by divers or robots.

In 1992, IEASM began mapping the area around the port of Alexandria and in 1996 they extended their research to include Aboukir Bay, tasked by the Egyptian government to discover Canopus, Thonis and Heracleion, all believed to have been reclaimed by the Mediterranean Sea. This research allowed them to understand the topography and circumstances that caused submersion of the area over time. The team used information from historical texts to establish the areas of primary interest. The survey of Aboukir Bay covered a research area of 11 by 15 kilometers (6.8 x 9.3 miles).

Beginning in 1996, the mapping of the Aboukir Bay took years. In 1999 they discovered Canopus, and in 2000 they discovered Heracleion. The site of the sunken city of Heracleion remained hidden in the Bay of Aboukir for so long because the remains of the ancient city are covered with sediment. The upper layer of the sea floor is made up of sand and silt deposited as it exits the River Nile . The team from IEASM was able to locate remains by creating detailed magnetic maps, which provided the evidence needed to finally pinpoint the location of Heracleion.

One of the most impressive finds at the sunken city of Heracleion in the Bay of Aboukir was the statue of a Ptolemaic era queen. It probably represented Cleopatra II or Cleopatra III, dressed as the goddess Isis. ( Christoph Gerigk © Franck Goddio Hilti Foundation )

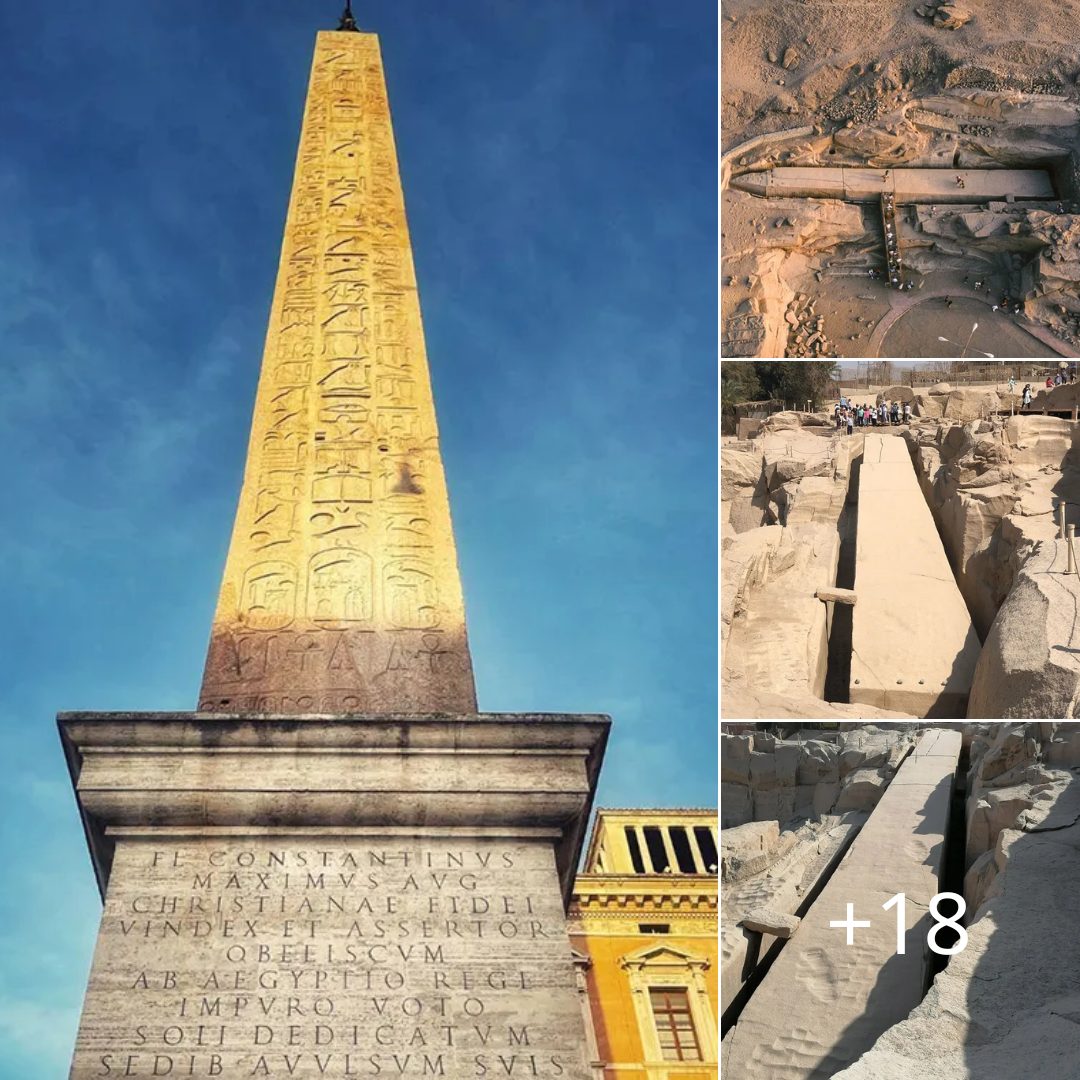

Now submerged under the waters of the Mediterranean Sea, in its heyday Heracleion was located at the mouth of the River Nile, 32 km (20 miles) to the northeast of Alexandria in ancient Egypt . The enormous city was an important port for trade with Greece, as well as a religious center where sailors would dedicate gifts to the gods. The city was also politically significant, with pharaohs needing to visit the temple of Amun to become universal sovereign.

Using cutting edge technology, and in collaboration with the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, IEASM managed to locate, map, and excavate the ancient sunken city of Heracleion, which was found 10 meters (32.8 ft) below water and 6.5 kilometers (4 miles) from the current-day coastline in the western part of Aboukir Bay.

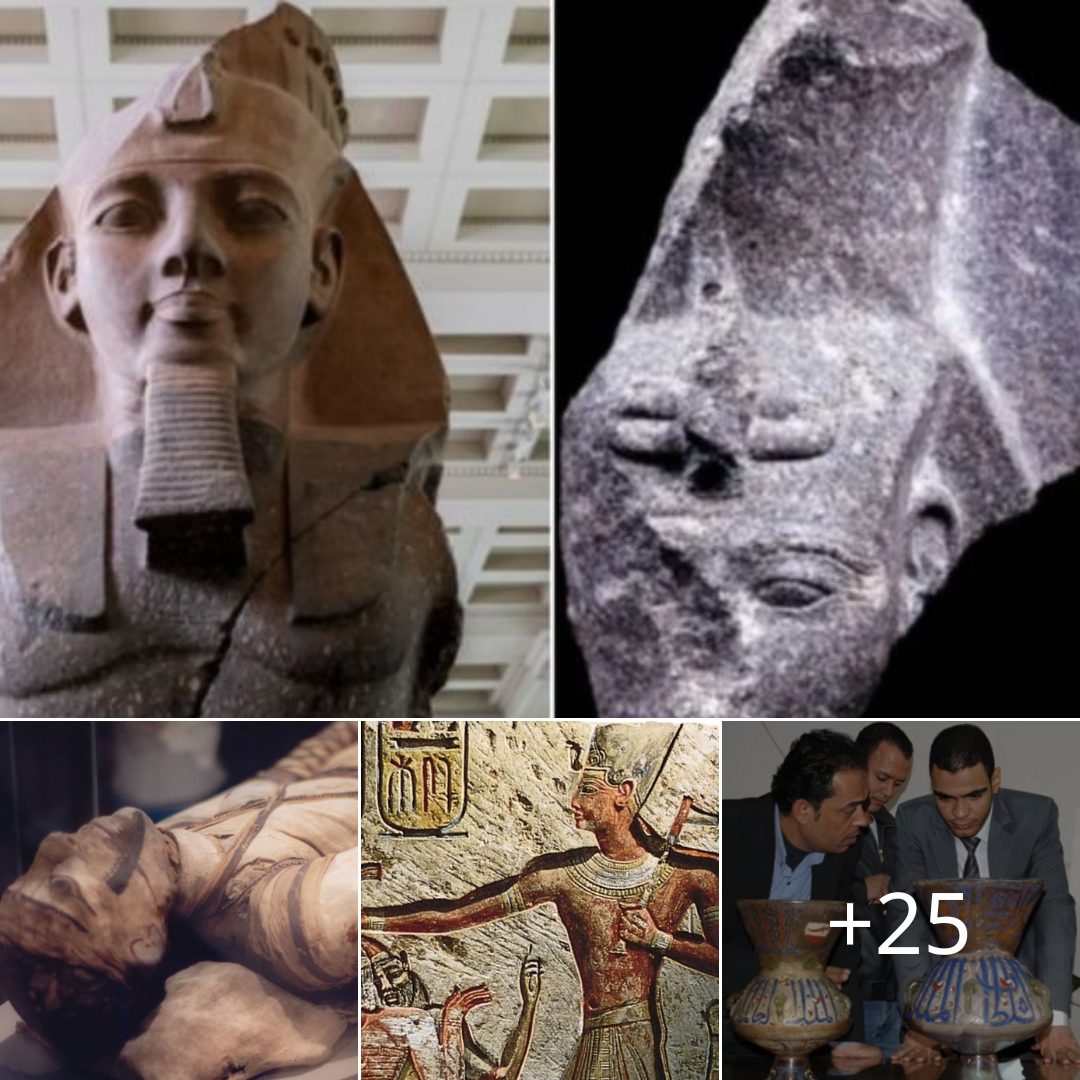

After removing layers of sand and mud, divers uncovered the extraordinarily well preserved city with many of its treasures still intact. These included the main temple of Amun-Gerb, giant statues of pharaohs, hundreds of smaller statues of gods and goddesses, a sphinx, 64 ancient shipwrecks, 700 anchors, stone blocks with both Greek and ancient Egyptian inscriptions, dozens of sarcophagi, gold coins, and weights made from bronze and stone.

The team discovered a sunken statue of a pharaoh on the Mediterranean sea floor near the great temple of ancient Heracleion. ( Christoph Gerigk © Franck Goddio Hilti Foundation )

Amongst the remains of the once great city, the underwater archaeologists discovered an enormous 5.4 meter (17.7 ft) statue of Hapi, the god dedicated to the inundation of the Nile. This was one of three colossal red granite sculptures discovered dating back to the 4th century BC. In 2001 the team also discovered an ancient stele originally commissioned by Nectanebo I some time between 378 and 362 BC, complete with detailed and clearly readable inscriptions.

The inscriptions on this ancient stele allowed the archaeologists to determine that the ancient cities of Thonis and Heracleion were in fact one in the same, Thonis being the name used originally by the Egyptians, and Heracleion being the ancient Greek name. From then on the ancient sunken city was known as Thonis-Heracleion.

View of the giant triad of 4th century BC red granite statues discovered in the underwater sunken city of Thonis-Heracleion. They represent a pharaoh, his queen, and the god Hapi. ( Christoph Gerigk © Franck Goddio Hilti Foundation )

Spectacular photographs of the discovery and recovery process reveal numerous statues and structures that once stood tall and mighty in the great city. One photo shows a Greco-Egyptian statue of a Ptolemaic queen which stands eerily on the seabed, surrounded only be sediment and darkness, while another photograph shows the face of a great Pharaoh peering up out of the sand.

In an interview with the BBC in 2015, Franck Goddio explained that the policy of the IEASM underwater excavations was “to learn as much as we can by touching as little as we can and leaving it for future technology.” At that point around 2% of the site had been excavated. The clay sediment from the Nile which has hidden the ancient city for so long also acts to protect the artifacts on the sea floor from the salt water.

In the case of artifacts which are removed from their hidden underwater sanctuary, IEASM takes a great deal of care to restore and preserve them on board their ships and in laboratories. In some cases, this has taken days, but in others, such as that of the enormous Hapi statue, this took two-and-a-half years.

Bronze oil lamp discovered in the temple of Amun in the sunken city of Heracleion. ( Christoph Gerigk © Franck Goddio Hilti Foundation )

Construida en el delta del Nilo, la ciudad en sí estaba atravesada por una vasta red de canales y se decía que era increíblemente hermosa. Apodada la Venecia del Nilo, Heracleion fue en un momento el puerto más grande del Mediterráneo. Las exploraciones del sitio han concluido que la ciudad probablemente perdió importancia gradualmente a medida que se hundió en el mar durante la segunda mitad del siglo VIII d.C. Esto plantea la pregunta de por qué se perdió una ciudad tan importante.

Las causas incluyen una serie de fenómenos geológicos y eventos cataclísmicos. El IEASM unió fuerzas con otras instituciones para realizar investigaciones geológicas que han demostrado que la cuenca sureste del Mediterráneo se vio afectada por la lenta subsistencia, el aumento del nivel del mar y fenómenos locales relacionados con la constitución del suelo en la zona, que en conjunto formaron el condiciones para que ciudades como Heracleion se hundieran en el mar.

Reconstrucción digital de cómo pudo haber sido Heracleion. (Yann Bernard / Fundación Hilti)

En 2005, el IEASM obtuvo permiso de las autoridades egipcias propietarias de los artefactos para organizar una exposición itinerante de los artefactos descubiertos. La exposición resultante, titulada Los tesoros hundidos de Egipto, recorrió las principales ciudades de Alemania, España, Italia y Japón. La exposición en el Grand Palais de Francia tuvo una media récord de 7.500 visitantes por día.

El Museo Británico unió fuerzas con Franck Goddio en 2015 para organizar su primera exposición de arqueología subacuática, que incluía alrededor de 200 artefactos descubiertos frente a la costa de Egipto por el IEASM entre 1996 y 2012. Para entonces, Goddio estimó que habían explorado solo alrededor del 5% del antigua ciudad de Heracleion, que se estima cubre un área de aproximadamente 3,5 kilómetros cuadrados (1,35 millas).

Según The Art Newspaper, Goddio afirmó que “esto sería una gran tarea en tierra, pero bajo el mar y bajo los sedimentos, es una tarea que llevará cientos de años”. Para comprender la escala de esta tarea, Heracleion es aproximadamente tres veces el tamaño de Pompeya y los arqueólogos han estado excavando ese sitio catastrófico en particular durante más de 100 años.

La exposición del Museo Británico, titulada Sunken Cities: Egypt’s Lost Worlds, también se presentó en el Institut du Monde Arabe de París en 2015, y en el Saint Louis Art Museum de Estados Unidos. Su última parada fue el Museo de Bellas Artes de Virginia hasta enero de 2021, antes de que los artefactos regresaran a Egipto.

El descubrimiento de Heracleion plantea importantes interrogantes sobre si las llamadas “ciudades míticas” existen en realidad. Si una ciudad que alguna vez se consideró un mito puede ser descubierta desde las profundidades del mar, ¿quién sabe qué otras ciudades legendarias hundidas del pasado se descubrirán en el futuro? Sólo el tiempo dirá.