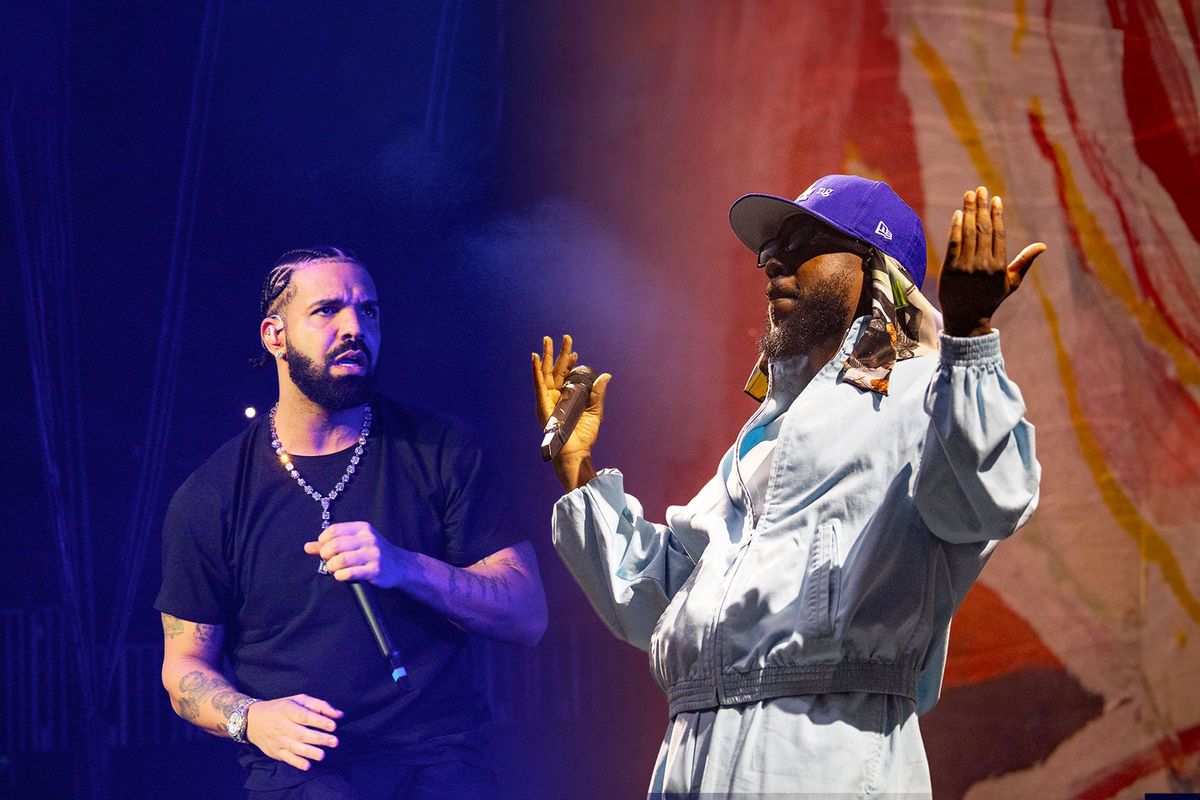

(JTA) — The recent “Great Rap War” between Black non-Jewish American rapper Kendrick Lamar and multiracial Jewish Canadian rapper Drake has been the subject of breathtaking headlines.

Drake and Kendrick Lamar have been exchanging extremely harsh, public, and fast-paced diss recordings over the last several weeks. These tracks have even attracted attention from major publications like the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times. I’ve been following those news as a scholar studying Jewish identity, race, and gender in popular culture. Drake is one of the major artists I’ll be looking at in my upcoming book, “Millennial Jewish Stars: Navigating Racial Antisemitism, Masculinity, and White Supremacy.”

My perspective: Although it is easy to write off the conflict between Drake and Kendrick Lamar as a publicity stunt or a pointless diversion from more important matters, it also highlights larger trends in how American culture views rap authenticity, race, class, masculinity, and Jewishness.

Lamar’s diss tracks have aired two main charges against Drake in this feud. First, Lamar cites rumors that Drake may prey upon underaged girls — for example, the 2018 revelation that Drake (then 32) had established a close texting relationship with actress Millie Bobby Brown (then 14). Drake is referred to in Kendrick Lamar’s song as a “pedophile” and “pervert” who “should be placed on neighborhood watch.”

Even though this is a serious 𝑠e𝑥ual allegation, the public’s response to the feud has mostly focused on Lamar’s second major charge, which is that Drake, a Jewish, Canadian, biracial, and former middle-class teen soap opera actor, is not authentic as a representation of the essential African-American culture of rap. The ongoing discussions in American society regarding the definition and resolution of instances of cultural appropriation, caricature, and exploitation are thus brought to light by Lamar’s lyrics.

The widespread belief that Drake isn’t Black enough, that his performances appropriate Black culture, and that Drake’s attempts to embody Black masculinity are repulsive or pitiful imitations of Black culture is reinforced by Kendrick Lamar’s diss tracks. Drake is referred to in Lamar’s lyrics as “off-white” rather than Black, and he is told to cease using the N-word and let Drake know that in the rap business, “you not a colleague, you a f—ing colonizer.” Lamar calls Drake a “pussy” and a “bitch,” undermining his masculinity as well.

Since Drake initially entered the American rap scene in 2006–2010, there have been circulating criticisms regarding his Blackness and manhood, and these criticisms have persisted alongside his incredible musical success. For instance, despite Drake’s 2021 Billboard Music Awards Artist of the Decade win, an astounding amount of internet “Drake memes” ridicule him, calling him “not really Black,” “not a real man,” and “not a real rapper.”

Rap authenticity has frequently been based on particular ideas of Black American hypermasculinity, a gender style that the African American Studies researcher Imani Perry refers to as “double-voiced,” long before the current controversy. This hypermasculine stereotype offers models of power and dignity to certain Black men who feel helpless in a racist society, while also titillating white suburban audiences with racist fantasies about hyper𝑠e𝑥ual and criminal Black males. However, this form of masculinity frequently necessitates dark complexion, which popular perceptions connect with harsher masculinity, and an underprivileged childhood in ghettoized Black districts of American cities, such as Compton, California, the hometown of Kendrick Lamar. This is true whether portraying racism or Black dignity.

Drake, real name Aubrey Drake Graham, is a light-skinned biracial man who was reared in a wealthy Toronto area by his Canadian Ashkenazi Jewish mother, defying the conventions of the industry. In addition, Drake performed as a teenager in the corny Canadian serial drama from 2001 until 2008

on the schmaltzy Canadian soap opera “Degrassi: The Next Generation,” in which he played an artistic and gentle middle-class student who eventually becomes wheelchair-bound and experiences erectile dysfunction.

In the context of American rap, all of these traits position Drake as an inauthentic Black man and thus an inauthentic rapper. For example, early in Drake’s career, CBS News’ Katie Couric illustrated the way that popular stereotypes of “soft” Jewish masculinity could undermine his rap credibility: When interviewing Drake in 2010, Couric immediately asked, “What’s a nice Jewish boy doing in a career like this?”

Even for viewers unfamiliar with stereotypes about “soft” Jewish men, Jewishness is often associated with whiteness, fueling the misperception that Jewish identity undermines authentic Blackness. Drake himself has discussed the perception: Early in his rap career, he told Heeb magazine, “I went to a Jewish school, where nobody understood what it was like to be black and Jewish.” While this miscomprehension led some of Drake’s classmates to question his Jewishness, it motivates some audiences today to question his Blackness.

But if Drake’s skin tone, class upbringing, Jewish identity and acting resume all distance him from rap industry norms, then his efforts to close that distance have often just marked him as even more inauthentic, and even as exploitative. Over time, Drake has striven to better align his image with the industry’s model of Black hypermasculinity. For example, he revealed new muscles after a regimen of bodybuilding in 2015 and he revealed his hair in new cornrows in March 2022.

Likewise, Drake has shifted towards fashion choices that evoke ghettoized Black communities and has begun to speak more consistently in African American Vernacular English, both in performances and in public appearances. However, these changes always risk coming off as contrived because Drake’s early interviews and “Degrassi” performances suggest that he grew up speaking and dressing in accordance with white Canadian middle-class norms.

Indeed, a long line of critics, including Kendrick Lamar, have disdained these changes as proof that Drake is stealing from Black culture or caricaturing Blackness in order to shore up his marketability. For example, in the recent diss track “Euphoria,” Lamar raps, “I hate the way that you walk, the way that you talk/I hate the way that you dress.” In the diss track “Meet the Grahams,” Lamar raps, “The skin that you livin’ in is compromised in personas.”

In the wake of this rap feud, time will tell how Drake may continue to modulate his relationship to rap industry conventions, and how his future self-stylings will be received by peers and audiences. But however his individual image evolves, Drake will likely remain a high-profile barometer for the wider debates over cultural authenticity, ownership, and theft that all performers (both Jewish and non-Jewish) must navigate onscreen.